As I’m writing this in late August, I’m looking at a forest of bamboo in front of me. No, I haven’t gone overboard and planted a bamboo patch in my small suburban backyard. These are dry bamboo poles diligently doing their job of supporting my dahlias, hollyhocks, tomatoes, raspberries and other such lanky inhabitants of the garden.

I feel that staking is one of those jobs that we tend to overlook when we restart our flurry of gardening activities in spring. Understandably so. Not all plants need stakes and, even if they did, this won’t need to happen for a few months. The stakes are just not that high, pardon the pun.

But I think that knowing which plants need staking is a good first step in planning our gardens, especially when we’re just beginning this wonderful journey. Knowing when they’ll need staking is also an important factor in the garden design equation.

Why should I stake my plants?

Here are some scenarios in which staking your plants moves from optional to mandatory.

You’re growing top-heavy plants.

I absolutely love dinnerplate dahlias. I love how boastful and showy they are. But I also know that the giant pom-pom flowers will definitely flop under their own weight. In a worst-case scenario, the weight will even cause the dahlias to snap.

So if you’re planting top-heavy flowers, such as dahlias, delphiniums or peonies, you have to be prepared to stake them.

You’re getting a lot of rain.

Rain is excellent for the lushness of a garden. But too much rain can also be detrimental. In addition to the fungi it helps proliferate, rain also adds weight to a plant’s surface. After three weeks of almost daily rain in June and July, even the most upright perennials in my garden were taking a deep and reverent bow.

I wish I’d had the forethought to stake or corral this oregano border in time. The extra added weight of rainwater caused the entire row to split in the middle and flop over the sides of the garden bed.

Your flopped plants are smothering their neighbors.

It’s not a big deal when perennials flop every now and then, as long as they get back up once they have dried. Right?

But the problem is when they flop on whatever is in their path, such as other plants. The shorter plants will be smothered or stunted through no fault of their own. So corralling the lanky buds in the garden early enough to prevent this is the best solution.

They may also flop over paths and sidewalks and become a slipping hazard.

You’re growing plants with brittle stems.

In my experience, this is often a problem with some of the annuals I’m growing. Even though they’re not top-heavy – in fact, their flowers are quite small and dainty – these plants just have very brittle stems that snap in stronger winds. This effect is usually compounded by a fairly weak root system, typical of annuals, that’s not strong enough to hold the plant upright.

Some cosmos varieties are guilty of this behavior, either snapping out of nowhere or leaning so close to the ground that the blooms are facing downwards.

Your garden looks untidy.

I’m quite a fan of an untidy garden, but up to a point. When the perennials have their feet in the border and their head flopped over on the pavement, that’s not a pretty sight. Neither is clumps of plants that have split in the middle and flopped in all four directions. Not to mention the inadvertent creation of horizontal tangles.

There’s a fine line between a messy garden and absolute chaos; most of the time staking your plants can make a difference between an eyesore and a backyard oasis.

How do I stake plants correctly?

Hopefully, my arguments for plant staking have helped you decide that this gardening job is worth the trouble. (If you’re not convinced, keep reading.) There are a few methods to do this, depending on the layout of your garden and the plants that need a bit of extra vertical support. If you walk into any gardening center, you’ll find shelves – sometimes even rows – of plant supports. So I admit that knowing which ones to choose can get a bit overwhelming.

I’ve simplified plant staking options into two categories.

Stake your plants using single canes.

In my suburban garden, where space is at a premium, using bamboo canes makes the most sense. I buy them in sets of five (longer ones) or ten (shorter ones); and since I take them out of the ground and store them dry over winter, I rarely have to replace them.

I prefer to use bamboo because it’s sturdy, flexible and it’s really affordable. If a pole breaks beyond any usage, I just throw it in my compost bin and it leaves no trace behind. But you don’t have to stick to bamboo. You can also find stakes made out of wood, metal or plastic.

Another good source of stakes is your own garden. A couple of years ago, I started saving the raspberry canes that I was pruning off to use as supports for my dahlias. As much as possible, I strip the spikes off to make them smooth before using them.

Simply insert the stake into the ground next to the plant, an inch or two away from the main stem. Then use some natural twine or string to tie the stem to the bamboo cane. Don’t damage the stem by tying your plant too tightly. It should still be able to gently sway in the wind, but without breaking. You can secure it in multiple spots if the plant is tall.

Also worth considering is the depth at which you plunge the stake. If you’re trying to prop up a heavy plant, such as a dinnerplate dahlia, stick the cane at least six inches (12 cm) deep.

Stake your plants with ring supports.

You’ll sometimes see them for sale as peony rings. These supports come in different shapes – hollow rings, semi-circles or a circular grid. Personally, I think tomato cages fall under this category as well.

Ideally, you’d stake this type of support in the ground when the plant is young. As the plant matures and fills out, it will grow through the circle or the grid which will then support it 360 degrees.

Ring supports work really well as preventative staking for plants that will become top-heavy (such as peonies and dahlias) or to corral plants that grow a bit lanky and unruly (such as foxgloves, Russian sage and Japanese bellflowers).

The advantage of using ring supports is that it’s generally a once and done job. You don’t have to keep adjusting and adding more (or taller) stakes as the season progresses. The disadvantage of using them is that they’re not very adjustable. You have to set them in place when the plant is young and can only remove them when the plant is nearing its end.

When do I need to stake plants?

Ideally, the best time to stake plants is when they’re too young to need it, in spring. This is called preventative staking and it will save you a lot of trouble in the long run. So if you get organized early, you can do what’s called preventative staking. When it comes to plants such as peonies, that need to grow through the ring support in order to showcase their full beauty, this is the ideal scenario.

In a more accurate gardening scenario though, late spring is when I have other things on my mind. Transplanting seedlings, taking cuttings, pruning perennials all take center stage. Staking plants is not even on my radar. Most of the time, I end up doing what’s called remedial staking, when I prop up mature plants if and when they need it. So I end up using a lot of bamboo canes to prop up mid-sized plants.

The one trick that always helps is to remember to size up the support (height-wise) because I’ll always end up tying it higher and higher as the plant grows. The one exception to this is some staking that I do at transplanting time. For example, for the dahlias that I started indoors in pots, I stuck the stakes in the ground at the same time as the tubers. I still had to upsize them as the plants matured.

How can I avoid staking plants?

That sounds like too much of a hassle. Can I avoid staking plants?

This was my exact thought process one summer, when I spent three consecutive weekends going back and forth to the garden center to buy more stakes. I was always underestimating how many plants would need staking and how soon.

If you see plant staking as a chore you’d rather skip, here are a few ways you can avoid it, starting with the planning stage of your garden.

Look for the mini version cultivars of your favorite plants.

In today’s plant market, it’s very easy to find different cultivars for almost every popular ornamental plant. If you want to avoid staking, look for cultivars that maintain a compact size. Words such as “little”, “mini”, or “dwarf” are usually a good indication of a variety that has been bred to stay small at maturity.

For example, opt for Black-eyed Susan ‘Little Goldstar’ or ‘Viette’s Little Suzy’ instead of the taller ‘Goldsturm’.

You can even find smaller versions of notorious floppers such as peonies. Look for ‘Fairy Princess’, ‘Little Red Gem’ and ‘London.’

Another trick is to buy cultivars that have been specially created for containers, even if you plan on growing them in full soil in the garden.

Keep in mind the sunlight requirements.

This is something I like to call “wishplanting” and I’ve been guilty of it myself over and over again. You fall in love with a plant that requires full sun, bring it home, then realize your garden only gets part sun. You plant it anyway, right?

Most of the time, this works just fine. At most, the only side effect will be fewer flowers or slower growth. But in some cases, it can also lead to plants growing overly tall and skinny in a futile attempt to reach for more sunlight.

Avoid overfertilizing your plants.

The best way to improve the health of your plants is by improving the health of your soil. And the best way to do that is by adding a layer of fresh compost to your soil in spring, as your perennials are starting to grow again. This allows your plants to take in balanced amounts of nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus.

However, when you use synthetic fertilizer, you’re giving your plants the equivalent of energy shots. Doing that a couple of times every season (depending on the plant) is fine. But overfertilizing, especially with feeds that are high in nitrogen and potassium, often leads to new growth that’s often leggy and that will eventually need to be propped up.

Avoid planting tall perennials in windy locations.

When we bring a new plant to the garden, we usually think about its sun and watering needs. We rarely think about wind exposure. What might be strong wind for a perennial might not even register for us. Unfortunately, this is one of those factors that is impossible to change. We can only adapt.

In a best-case scenario, we can plant windbreaks such as hedges, shrubs or trees. But when these additions don’t make sense in the garden, we have to adapt by choosing perennials that are lower to the ground. They are less likely to sway and snap if the wind gets too strong.

What plants might need staking?

I’ve compiled a list of plants that will most commonly need staking. Please note that I left out perennials that have a climbing pattern and other vines, such as clematis, jasmine and honeysuckle which will always need a trellis to climb on.

Most of the times, these plants will need to be supported by stakes:

Oriental poppies (Papaver orientale)

Peonies (Paeonia lactiflora)

Delphiniums (Delphinium)

Larkspur (Consolida ajacis)

Dahlias, especially the dinnerplate cultivars

Goldenrod, especially the giant varieties (Solidago gigantea)

Crocosmia

Foxglove (Digitalis, especially Digitalis grandiflora)

Sneezeweed (Helenium)

Zinnia

Hollyhocks (Alcea)

Tall yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

Annual and perennial sunflowers (Helianthus)

Japanese anemone (Anemone hupehensis)

Sweet pea flowers

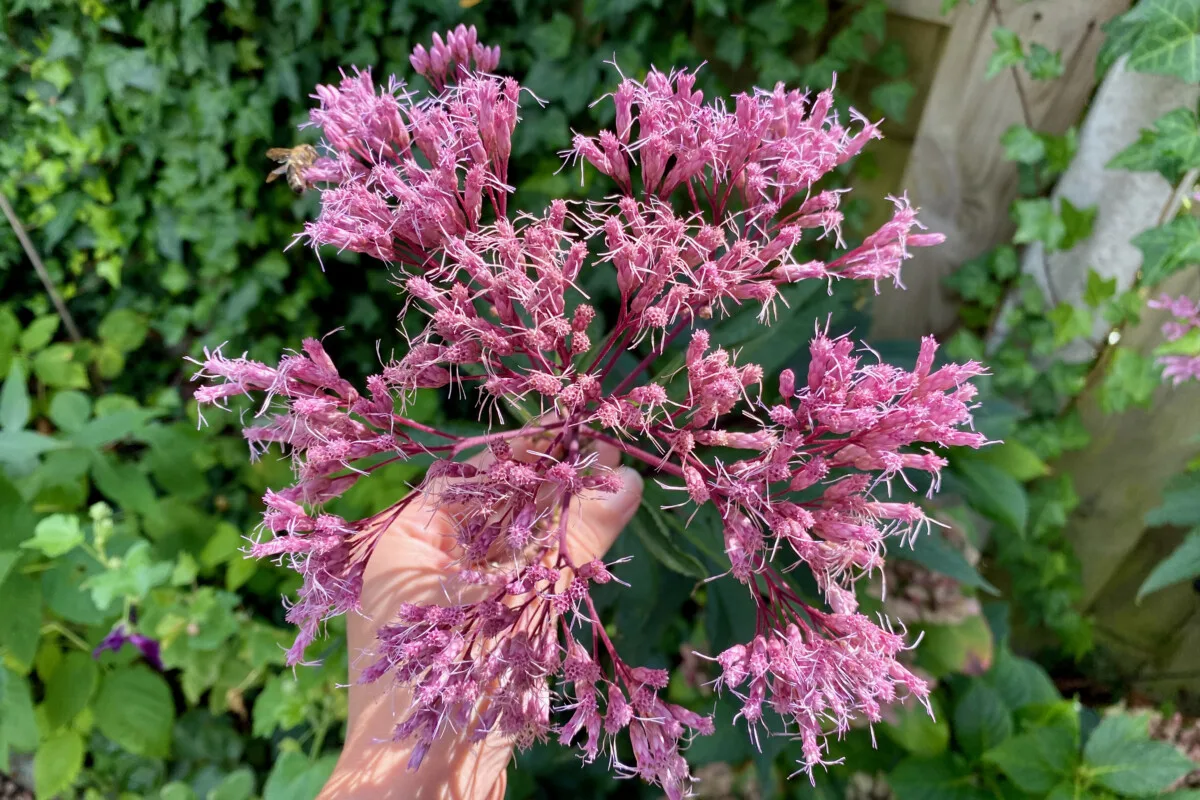

Joe Pye Weed (Eutrochium)

Sea holly (Eryngium)

False indigo (Baptisia)

Garden phlox (Phlox paniculata)

Russian sage (Perovskia)

Tall marigolds (Tagetes erecta)

Tall coneflowers (Echinacea)

Peruvian lilies (Alstroemeria)

Cosmos (Cosmos)

Tall asters (Aster)

In the end, I realized that I approach staking plants with the same attitude I have towards a lot of gardening jobs: as a process of trial and error that has plenty of room for creativity and resourcefulness.