It seems like only yesterday I was writing an article on how to prepare your roses for the winter months. While at the same time, it also seems like this drab and dreary franken-season has been going on forever.

But now that the temperatures are rising (ever so slightly), the days are getting longer (faster and faster) and the forsythia is in bloom, it’s time to do a bit more rose care.

In spring, this will be first and foremost pruning.

The 3 Principles of Pruning Roses

There are several schools of thought about pruning roses. And even when you go to the experts (Master Rosarians, they’re called), there are pruning guides and rebuttals to guides and rebuttals to rebuttals. No wonder hobby gardeners are more confused than ever.

So instead of fretting about what specific rules I should give more credence to, I focus on a few basic principles:

When I prune roses, my main goals are to:

- Remove dead, damaged or diseased canes;

- Remove crossing stems;

- Generally open up the plant to get better airflow and light.

It makes sense to do the pruning in this exact order. Let me explain these three principles a little more in depth.

Step 1: Removed the dead, damaged and diseased stems.

This is what you start with. Removing the dead weight first will give you a good indication of what you have to work with.

Dead canes are easy to recognize. They are either brown, gray or black. The wood is clearly dead and nothing will grow out of it. Sometimes, the dead wood extends from all the way down to the crown.

In other cases, only the top of the cane is dead or dying. In these instances, you can keep cutting it off until you find a healthy white or light-green center (called a pith).

Damaged canes are not exactly dead, but they’re on their way. Sometimes, the damage may have been caused by windrock or heavy snow and ice fall during the winter. Other times, it may have been mechanical, caused by the canes rubbing against fences, support structures or each other. At this point, you can cut just below the damage, but just above an outward facing bud.

Diseased canes are not always easy to spot. Look for discoloration or a rougher texture on the surface of the canes. It’s important to remove these stems because disease can spread easily from one stem to another, but also from one rose to another.

You may also notice new growth that’s already diseased. The new shoots that you leave on the rose should always be green, red or the occasional orange. Any new growth that’s black, brown or gray needs to go.

Step 2: Remove crossing branches.

Ok, this one seems a bit counterintuitive because we’re now starting to remove healthy canes. But whenever two or more canes are starting to intersect, one of them has to go. That’s because the longer the stems rub against each other, the more likely it is for them to get lesions that will eventually allow diseases in. Over time, this will lead to the weakening of the entire plant.

But which of the two crossing branches should you remove? If one of them is growing inwards, towards the center of the plant, that’s the one that has to go. If both of them are growing outwards, remove the one that looks weaker. But if you can’t figure out which one is weaker, keep the one that has more buds growing towards the exterior of the plant.

Step 3: Prune to open up the plant.

Two things to remember about roses: they love the sun and hate high humidity. So our aim with this third step of pruning will be to open up the center of the plant into a vase-like structure.

This will serve two purposes: more light will reach the plant and more airflow will blow through the plant. Both of these factors will help prevent or minimize the damage caused by moisture-loving fungi and diseases. Powdery mildew and black spot are two of the most common problems that rose gardeners face, and the earlier we can prevent them, the better.

Start by removing the older stems in the center. Depending on what type of rose you’re growing, you’ll want to remove them all, only half, or just a third of the older stems, number-wise. The age of the plant is also a factor to consider. The younger your rose, the fewer canes you’ll need to remove.

Allowing more direct sunlight into the center of the plant will encourage new cane growth from the crown. And once the rose is in bloom, you’ll notice that this vase-like shape looks much more pleasing to the eye than a tangle of bunched up stems.

Whenever you cut into a rose cane, it’s good practice to cut at an angle above an outward-facing bud. This way, you’ll ensure that the new growth doesn’t crowd towards the center of the plant.

My advice is to start your pruning a bit more timidly, especially if you’re new to growing roses. You can always prune back more, but you can never unprune.

That’s it! If you follow these principles, you’re more than halfway there.

The other “half of the way” comes with practice (read: mistakes), trial and error and knowing what kind of roses you’re growing in your garden.

Should I prune my rose this spring?

Now here’s the million dollar question. This depends on what kind of rose you’re growing, how many times a year it blooms and on what stock (old or new). A few other important factors include your climate, the age and size of your rose and even the rose’s location on your property.

First of all, you shouldn’t be pruning new roses anyway. A rose needs a couple of years to become established; so it’s best to postpone the pruning for the first two years after you’ve planted your rose. This way, the rose will focus on developing a strong root system rather than on growing above ground and blooming.

In a nutshell, all roses fall within one of the following groups:

- Species roses (also known as wild roses)

- Old garden roses (also known as heirloom roses or historic roses)

- Modern roses

1. Species Roses

Species roses are the closest you can get to rose ancestors growing in the wild. Think of them as the grandparents of modern roses. They basically grow as prolifically as brambles and do very well in the shade and in poor soil. You’ll be able to tell them apart because they have very simple but very fragrant and abundant flowers. The flowers typically have five petals in muted pastel colors.

Most species roses flower once a year on last year’s growth, so they do not need any spring pruning. Instead, you should prune right after this year’s blooms are done flowering. However, think ahead about what you want in your fall and winter garden. Leaving some flowers on the shrubs will result in having beautiful rosebud winter ornaments. Not just for your enjoyment, but to feed the birds as well.

When you do prune in the summer, in addition to dead, diseased and damaged stems, you can cut the oldest wood from the base in order to promote young shoots. You can also shorten the side shoots by about a third.

2. Old Garden Roses

If species are the grandparents, the Old Garden roses are the parents. Any rose that was in cultivation before 1867 is considered an “Old Garden rose.” That’s not just a random date, but the year when the first hybrid rose (‘La France’) was introduced into cultivation.

Old garden roses are very resistant to diseases and pests. In addition to that, they smell absolutely divine and are true pollinator magnets.

Old Garden roses can be single bloomers or repeat bloomers, and knowing which one you have can make all the difference in timing your pruning. And to make matters more complicated, Old Garden roses come in a variety of shapes and sizes – from shrubs to climbers.

The once-bloomers in this heirloom category are Alba, Centifolia, Gallica, Damask and Moss.

These once-bloomers flower early in the year, generally in spring and early summer. You can prune them lightly after they’ve flowered, with the goal to remove the oldest stems that are no longer as productive.

Generally, avoid giving Old Garden roses a hard prune, so don’t cut off more than the top third of each plant. If you don’t remove all the spent blooms in the fall, you’ll have plenty of rosebuds for winter garden interest. You can remove the rosebuds in spring.

The Old Garden repeat bloomers are: Bourbon, China, Hybrid Perpetuals, Noisettes, Portlands and Teas.

These repeat-flowering roses bloom on both old and new growth. You can tidy them up in spring, before they flower on old stock. For most of them, you can lightly shape them after the first flush of blooms. But you should leave the hard pruning until the second flush of blooms is over. Again, start with dead and diseased branches. You can remove about a third of the old canes to open up the plant, and any canes you may need to in order to reshape the plant. Prune the remaining canes by about a third.

3. Modern Roses

Here is where things get a bit tricky. Modern roses, as I mentioned above, are any roses that have been introduced after 1867. So these “young kids” may have been born in the 1900s and still be considered “modern.”

In the United States, the American Rose Society started keeping track of cultivars in 1930. Even back then, their database consisted of about 2500 worldwide registrations. Crazy!

But it gets better! At the time I’m writing this, there are over 37,000 rose cultivars registered in the Modern Roses database. That’s just MODERN roses, so it doesn’t include species roses or Old Garden roses. Is it any wonder that we’re confused about how and when to prune roses?!

If you’re buying roses nowadays, they’ll most certainly be Modern roses. But there are still some heirloom rose farms that have moved their operations online. So the sturdy and fragrant Old Garden roses are still available for sale, though not as common.

But if Old Garden roses were so perfect, how do they differ from Modern roses?

Modern roses have been selectively bred for one or more of the following characteristics:

- They are usually repeat bloomers;

- They are in bloom for a longer period of time;

- The have larger blooms in brighter colors;

- They last longer when cut and used in flower arrangements.

That sounds like the perfect rose, doesn’t it? Well, there are some drawbacks: Modern roses barely have any fragrance left. And since they’re newer cultivars, they are not as resistant to diseases and they’re less hardy than their heirloom parents. And since they don’t go truly dormant, they’re more likely to suffer from winter damage. That’s why they need more winter and frost protection than heirloom varieties.

When it comes to pruning, Modern roses generally need a harder prune.

As a general rule, the higher you prune, the earlier you’ll get flowers. But if you prune the canes lower to the ground, you will delay your blooming period, but you’ll get bigger blooms.

Let’s have a look at the main classes of Modern roses, keeping in mind that every class has a myriad of cultivars.

Hybrid tea roses

We learned that tea roses are Old Garden roses. But hybrid tea roses are Modern roses. In fact, they are the oldest Modern roses and the most popular class of roses in gardens nowadays.

Gardeners gravitate towards hybrid tea roses because the plants have a long-blooming season, large flowers (usually one per stem) and a tall, imposing structure.

Hybrid tea roses need a heavy prune in the spring, just when the buds start to swell up and break dormancy. Depending on where you live, the pruning window spans from mid-February to mid-April; so even when you think you’ve missed the window, there might still be time to prune.

Start by removing dead, diseased, dying and crossing canes. If there’s any sucker growth (canes growing out of the root stock), remove those as close to the main root as possible.

Then it’s time to thin out the center of the plant. Cut out some of the oldest shoots growing from the center of the bush, even if they’re not diseased. Hybrid tea roses can reach ten years or older, but most of the abundant bloom is carried by canes that are 2-4 years old. So that’s what we want to have most of at any given time.

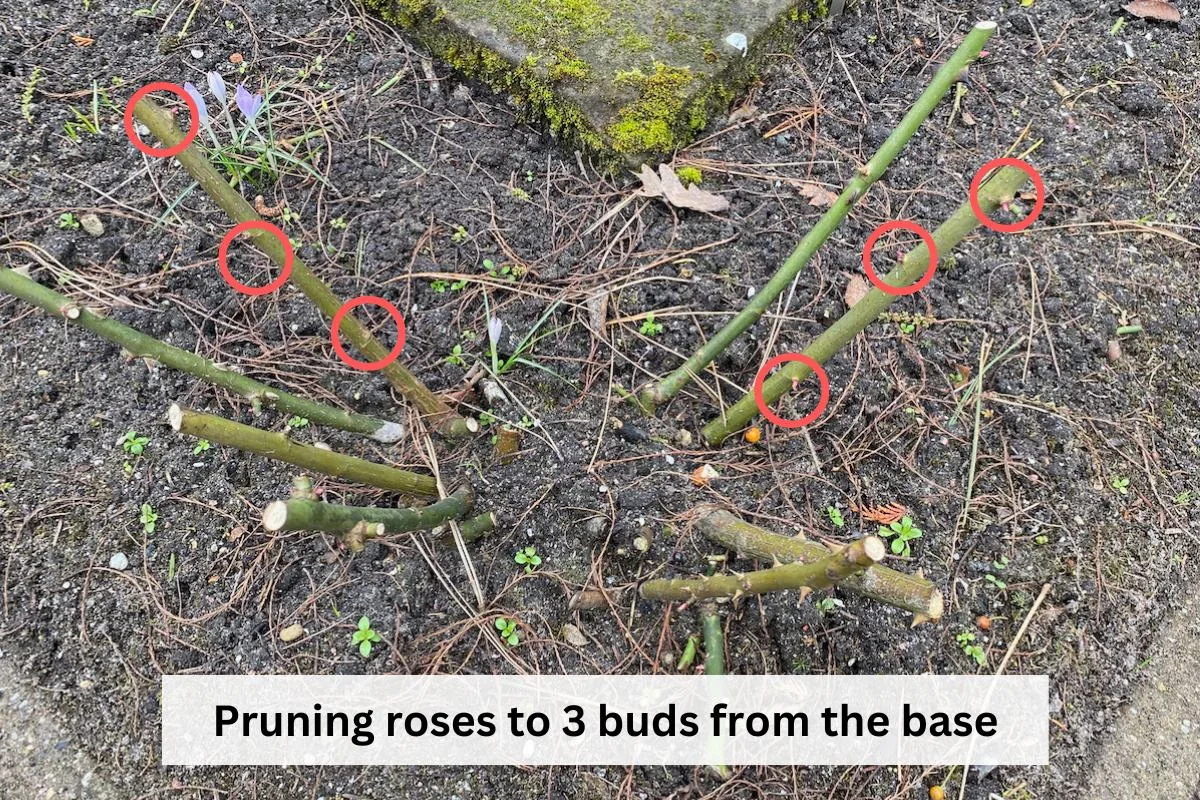

Now that you have some young canes left, it’s time to shorten them back. Cut back the strongest ones to about three to five buds from the base. Five buds from the base often translates to anywhere between 10 and 18 inches, depending on the cultivar you’re growing. Just count the buds. It’s ok to cut lower (3 buds) or higher (6 buds) depending on your preference and the shape you want to give to the rose. Then cut the remaining, less vigorous buds down to two-three buds from the base.

Make sure you cut right above outward-facing buds every time, to discourage overcrowding towards the center of the plant.

Polyantha (aka Rosa multiflora)

Even though they were introduced in the late nineteenth century, Polyantha roses are considered Modern roses. The plants grow vigorous and rich, often as shrubs, but have smaller flowers that will stay in bloom for a very long time from spring until fall. Some Polyanthas remain compact, while others have a rambling habit.

Polyanthas are really low-maintenance and disease resistant, so they don’t need too much pruning. They do need a tidy up in spring though. Remove the dead, diseased and crossing wood, then shorten the remaining young canes by removing a quarter or a third of the top growth. As usual, always cut back to an outward-facing bud.

Floribunda

Floribunda are a cross of Polyantha and hybrid tea roses. That’s why floribunda are very similar to hybrid tea roses in their care and maintenance. The only major difference is when it comes to bloom and, to a lesser degree, height.

Hybrid tea roses have large blooms, often one to a stem, while floribunda have smaller, clustered blooms. Hybrid tea roses grow taller, while floribunda tend to stay lower to the ground. Due to their masses of flowers and thicker growing habit, floribunda can often be used as a hedge if planted close enough.

We prune floribunda in the same order that we prune hybrid tea roses. The only difference is that we don’t need to prune floribunda roses as low to the ground. Leaving them longer, with more buds on, will ensure that we have the abundance of flowers that floribunda are known for.

So start by removing dead, damaged, diseased and crossing branches. Then prune some of the oldest canes right from the base. But when you cut back the remaining healthy canes, don’t prune as hard. Just cut back to encourage forming flower clusters at a height that’s suitable for your garden. And if you’re using floribunda as a hedge, that will be on the higher side.

Grandiflora

Grandiflora are a mid-twentieth century hybrid between hybrid tea roses and floribundas. These roses generally grow as shrubs, with flowers that are similar in appearance to hybrid tea roses. But the flowers grow in small clusters, which is a trait it inherits from floribunda.

Grandiflora are repeat bloomers (more like perpetual bloomers) which need a good prune in early spring. The pruning method is very similar to that of hybrid tea roses. Prune hard for large blooms (but fewer of them). After you’ve removed the dead material, select four to seven older canes (depending on how old your rose is) that create a vase-shaped structure with an open center. Prune out the rest of the older canes and shorten the remaining canes by about a third.

Climbing roses

I’m giving climbing roses a separate category, even though “climbing” is not a separate class, but rather a growing habit. So climbing roses can belong to grandiflora, floribunda or even heirloom roses. The trick with climbing roses is to first determine how many times a year they bloom before you do any pruning.

Climbing roses can be once-blooming or repeat-blooming.

Once-blooming climbing roses will only bloom once a year (generally in early summer) on the previous year’s growth. It’s better not to prune them in the spring. Only when the blooms are gone for the year should you prune them and train them. Remove the oldest unproductive canes, then cut back the remaining canes down to a bud.

Usually climbing roses are trained horizontally to a fence or a trellis to maximize the number of blooms coming from each stem. The canes of climbing roses are usually thinner and much more flexible than those of hybrid teas.

Repeat-blooming climbing roses are the ones that need a harder spring prune. Leave the main canes in place unless they’re old and have stopped producing quality blooms. If any of the older canes looks barky and desiccated, then it’s time to cut it down to the root stock. Choose another nearby cane to replace it as a framework cane.

Then prune down the flowering laterals that spring from the main canes down to about three to five buds, depending on the size trellis you’re training them on. Retrain and retie the canes, if needed, fanning them out as much as possible. As always, remove the dead, diseased and weak growth.

I think that when it comes to pruning roses in the spring, patience is key. It takes several years to get acquainted with what kind of roses you’re growing and what their needs are. Don’t be discouraged if it all sounds confusing. Part of what makes gardening fun and rarely boring is the experimenting nature of it. If the results lead to profuse blooming, that’s even better.